The cathedral in Santiago de Compostela is known for the botefumeiro, a ceremony that involves swinging a person-sized censer back and forth across the north and south transepts of the church. While the smoldering incense fills the space, powerful chords from the organ resound through it, and, though kind of a spectacle, it is a cherished and storied part of the mass there.

I experienced the botefumeiro but indirectly, through filters, screens. As soon as the ceremony started, as soon as the monks began loading the censer with fuming coals of incense, the moment and moments, in all of their history and phenomenality, had to, needed to be, recorded, saved, loaded into the Cloud away from time’s meddling. There I stood in the pew, surrounded by walls, roofs and relics over 1,000 years old, tens of meters away from the alleged remains of St. James, friend and follower to Jesus Christ, taking part in a ceremony of a caliber and form the likes of which I would probably never see again. And there I watched that ceremony, in that space, on bright little rectangles held up by hundreds of hands.

Which is to say, in a way, that I didn’t watch it at all. Or at least, if I watched it, that I didn’t experience it. Leaving aside the obvious point that — call me a traditionalist — phones and cameras have no place in a religious service, there are things about the nature of experience that the phones bastardize. Much of the time, though not always, the wonder and beauty of experience comes from doing it with others. The sociologist Émile Durkheim made a compelling argument that our idea of the sacred, indeed the foundation of religion itself, came about as a result of the feeling we get when we get when we take part in things with others — that sense of something greater than ourselves — which he called collective effervescence.1 We might feel this during a church service, a sports game, or even a concert.2 The important thing about collective effervescence is that people are doing something together, are focused on the same worship, ritual, ceremony together, and in the unity of that sameness and intent, a deep connection with the others can be formed.3

The issue with the phone in these contexts is that the phone is fundamentally an object of individuality. Yes, most of the time we use it for social purposes, but it is always for our social purposes. We text our friends and family, and neurotically check the inbox of our email account. And when we take photos and videos, when we seek to capture our moments endlessly and incessantly, it is with the intent to capture it for ourselves, to have in our memories, to share with our myopic worlds.4 So what becomes in these collective spaces, in these spaces where a real chance exists for something special to happen between groups of strangers sharing an extraordinary experience, is a segmentation and an isolation, the reduction of a collective into a lump of individuals.5

There is also something lost when we are never confronted with having to recreate, retell our experiences. Homo sapiens has been trying to record and transmit experiences to one another since our species’ inception, and for approximately .01% of that time span, we have been doing so by way of “exact” replication — photos, videos, etc. For the other 99.99% of that history, we have done so by way of inexact replication — stories, songs, art, performance etc. Before the standardization of photo and video, the only way people could share and preserve experience was after the fact. The transmitting, then, became an act of creation. People turned the experience into a story, engaged their imagination, found the right language to describe what they saw and did.

I’m not saying this isn’t possible with photos and videos. “A picture is worth a thousand words,” so the saying goes, and that can be true. Photos and videos can give rise to and enhance retellings of experience. I love scrapbooks, photo albums, video compilations, all of the ingenious ways people have come up with to artfully convey their doings and happenings, and I love using these things and sharing my life through these mediums. My issue is with the quantity, the proliferation of photographing and videoing any and all things. A picture is worth a thousand words, but a thousand pictures doesn’t leave room for any words.

I think the impetus to constantly capture, save, record etc. comes from two places. The first is the desire to share with others. Humans are social animals; we like communicating, telling experiences, exchanging information, knowledge and our lives’ happenings. This ability having been given to us through the phones, we take full advantage by — with differing levels — recording, photographing, snapping and sending our life’s moments. Social media has meant that we feel almost obligated to do this, to show off and announce what we are seeing and doing in real time, to ensure we have a visible footprint in the highway of the digital world. The second impetus is existential. The fleeting nature of life and the moments that compose life is a troubling reality. We won’t get back the 5th birthday of our child or the day we graduated college or the 10 seconds of that whale breaching on that tour during the trip to Iceland. And memory is frail and untrustworthy, unreliable, fated to wither and disappear with the ages. The digital photo or video, however, exists forever on our device, on the Cloud, as shiny, saturated and unchanged through the decades as from day it was shot.6

In my early teens, I went to the Galapagos Islands. I brought along a GoPro that a friend let me borrow, taking it with me on every snorkel outing. I spent all of my time trying to get shots of sea lions and penguins, fish and turtles, and this meant often chasing after these poor animals and shoving my little camera in their faces. Everyone on the trip did some version of this with their own cameras and devices, except one skinny, bald, and soft-spoken older man. I recall asking him about this, and he told me something along the lines of ‘I take pictures with my mind.’ This has always stuck with me, and when I think about it I have to ask myself — who experienced that trip more? Who lived those dives, those sea lions and penguins more? The one who knew he wouldn’t get to see any of it again, or the one who spent the dive trying to preserve those moments so as to see them again?

“As far back as 1901,” writes the photographer Sally Mann in her memoir, “Èmile Zola telegraphed the threat of this relatively new medium, remarking that you cannot claim to have really seen something until you have photographed it. What Zola perhaps also really intuited was that once photographed, whatever you had ‘really seen’ would never be seen by the eye of memory again. It would forever be cut from the continuum of being, a mere sliver, slight, translucent paring from the fat life of time; elegiac, one-dimensional, immediately assuming the amber quality of nostalgia: an instantaneous momento mori. Photography would seem to preserve our past and make it invulnerable to the distortions of repeated memorial superimpositions, but I think that is a fallacy: photographs supplant and corrupt the past, all while creating their own memories. As I held my childhood photographs in my hands, in the tenderness of my ‘remembering,’ I also knew that with each photograph I was forgetting.”7

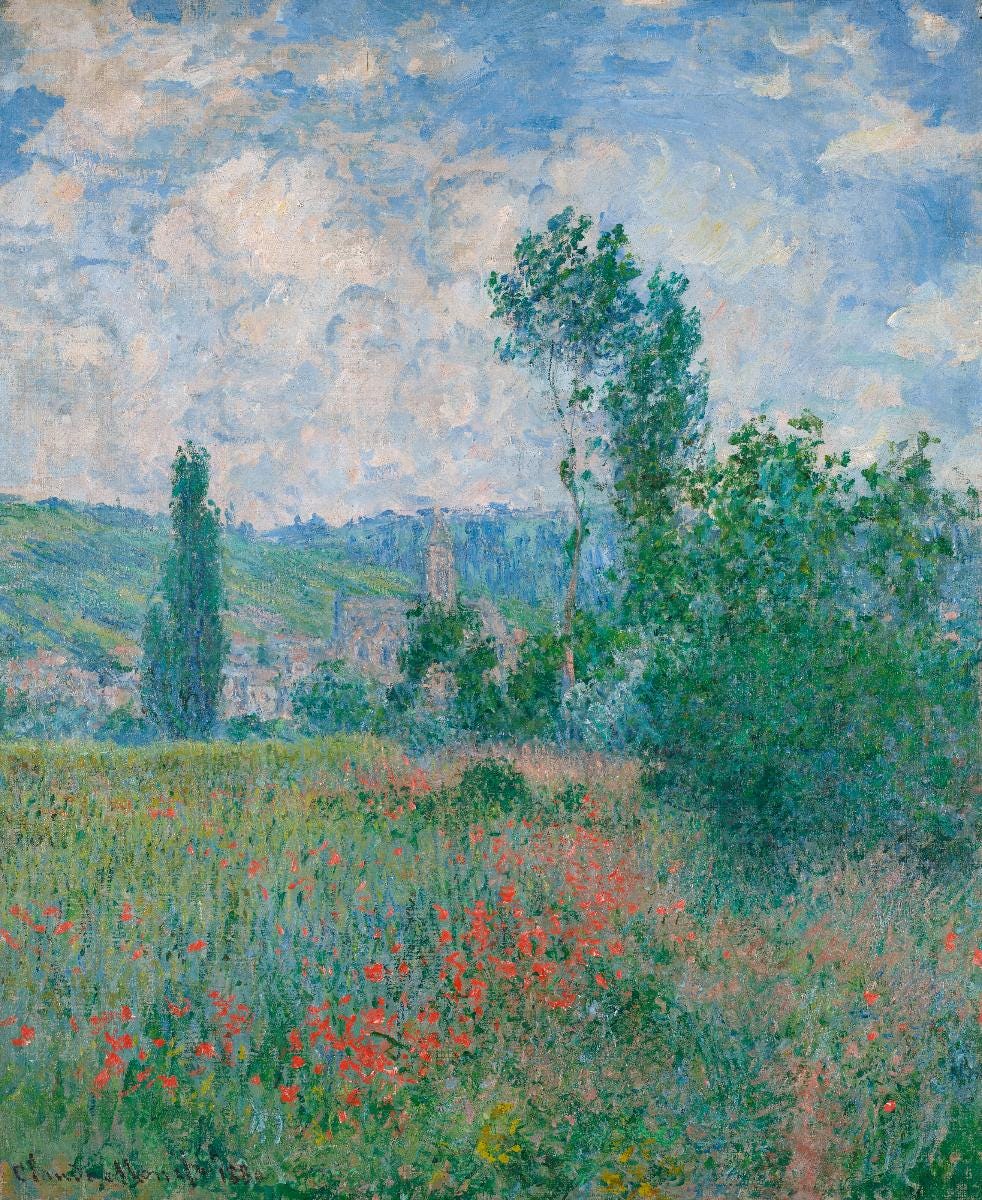

It’s an interesting thought, that each photograph constitutes a forgetting. That for all our efforts at preserving, snapping, shooting, filming and capturing, we lose something in the name of recollection, recollective ability, memory. Because the past seems to have a life of its own; it grows, changes in its shades and tones in our mind, and the memory we relive through the years is not the same as the event itself. It is subject, as Mann puts it, to the “continuum of being,” which means the memories are actually free, open and fluid to evolve, appear in a different light as we do. There is a beauty in this, the same beauty as the story that sees new iterations and additions across time and people, the song who finds new words in its lyrics, memory and experience that breaths, that gives rise to ever new thoughts and remembrances.

We are not like the unchanging and unaffected photos and videos; the selves and beings we are aren’t stagnant entities. Kierkegaard’s notion of the self was as a being who becomes, who is in a state of becoming such that who we are is a process, a striving, an unfinished project. “The human being,” he writes, “is Spirit. But what is spirit? Spirit is the self. But what is the self? The self is a relation which relates to itself, or that in the relation which is its relating to itself. The self is not the relation but the relation's relating to itself. A human being is a synthesis of the infinite and the finite, of the temporal and the eternal, of freedom and necessity.”8 Another essay could be devoted to unpacking this short excerpt, but the main point is the idea of the fluid self, a “relation’s relating to itself,” where the verb relating implies a fundamental process, continuance. And the way we relate to ourselves, in thought, in writing, is done by recollection and reflection. We take up our past, so to speak, so as to be the being who lives it, who makes it our own and realizes it as part of our being.9

Contrast all of this with Snapchat, dutifully informing us what memories we made one year ago to the day; with iPhotos showing slideshows of weekends with friends; with social media accounts offering windows into old selves and personas long outgrown. I wonder; is it good, is it positive to be constantly shown and reminded of the past, of this past? If part of the promise of being human is change, upward growth, betterment, becoming, don’t these frozen memories act as a cage to that very ideal? If Kierkegaard’s self says “I am who I will be,” it’s the prisoner of memory’s that says “I am who I was.” And I worry more people believe and live out the latter than the former.

On a walk around my neighborhood the other day, I came upon a rainbow. The evening was dark and stormy, and there, amidst the soft orange light of dusk, was the colored arc. After the initial sense of wonder, I, inexplicably, without thought or conscious intention, reached into my pocket for my phone to take a photo. Fortunately I had left my phone at home, but the impulse troubled me. Why? Why was I going to take a photo of this? For whom? In order to say what? Maybe it was because no two rainbows are ever the same. I wanted to preserve it for the same reason people preserve sunsets and sunrises; they aren’t always sure, and when they happen they are unique. But this remains unsatisfactory because nothing about the appearance in itself is answered. Why is this rainbow different than all the others I had seen before and will see again? The photo, actually, freezes the phenomenon for me so that I never have to go about answering that question. If I did go about answering it — and I started to try on this particular walk — it would mean drawing from all my senses, it would mean creating an image through language, and this could mean the language of words, but also the language of art, music, etc. I would have to cultivate my ability to storytell, recreate, express, covey the essence of this rainbow, and simultaneously be okay with losing it, with letting my memory and sharing of it be imperfect, because, well, we are imperfect, doomed, fallen, fallible, fragile, uncertain, all of it, and both our absorption in the Device and our frantic efforts to preserve all through the Device allow for a convenient obscuring of this.

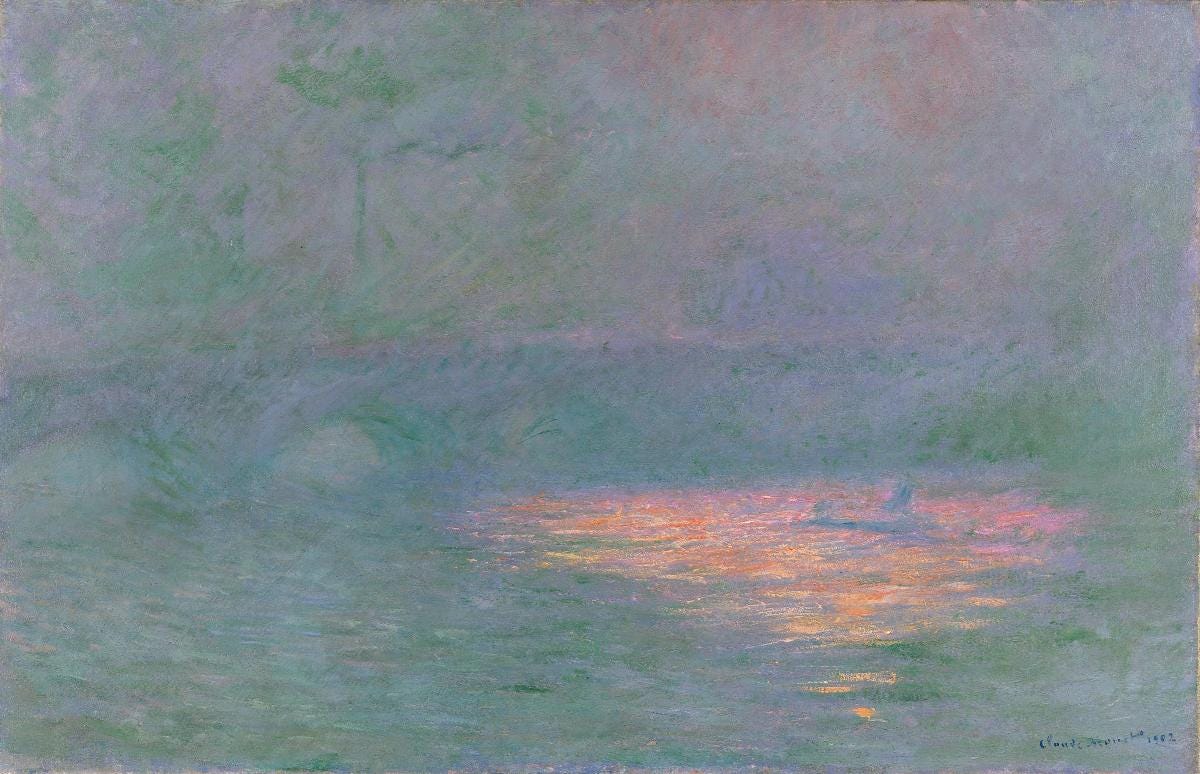

It seems that this tirade is coming to the same end as nearly all the now-tired tirades against the phone and tech and their robbery of Life from us, which is to say that we have to find some new and different way of using them. And I’m not sure what that looks like. Leaving it at home on a walk is a decent start, I think. Watch a sunset and just do that, watch. With your own eyes and soul. For myself, I’m really hoping I can rewire my impulses to not be enslaved to my little pocket time/moment-preserver. Gelassenheit is a German word Heidegger does much with. It translates to something like releasement, openness, a “letting-be.” The will, the same will that is operative in the act of capturing, sharing, preserving, shooting, filming, snapping, is absent in Gelassenheit. It is being open to the transcendent, to God, to the wonder of a summer’s sunset or rainy day’s rainbow, to existence and time as they present before us. Moments passing and changing, moments released into being what they are, moments not saved in exactness but received in impressions.

E. Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. Of course I’m not doing much justice to Durkheim’s complex ideas in this essay, but the general sentiment is that religion is fundamentally social. Durkheim studied aboriginal groups and determined their worship of certain totems — sacred symbols and images — to be representative of their clan, and deduced that what was really happening was the clan was worshipping itself.

Durkheim probably wouldn’t agree with this extension of his theory, because a lot of it is centered on the idea of ritual, and it isn’t clear what rituals, if any, are present in the modern pop concert, to give one example. Sports I think are different, and I have certainly met groups of fans who are as fastidious in their commitment to a team and have such a ritualized worship of that team that you are forced to seriously consider what they are enacting as fitting a definition of religion. This question of whether things like sports “count” as religion is and has been an ongoing debate in the study of religion for a while.

For better or for worse. “Losing yourself” in the group/mass so to speak, while incredibly powerful and often positive, can be negative. Like a mob. There’s a nice book by philosophers Hubert Dreyfus and Sean Kelly called All Things Shining, where they talk about a necessary balancing act in regards to collective effervescence, where you reap the benefits of joint participation/worship, but not so intensely that your sense of self is swept up irretrievably in the groupthink. Probably easier said than done.

And without consideration for the experiences of the people behind and around you, who now have to watch the event unfold on your phone or hear your recording of it or whatever.

And Durkheim’s biggest point is exactly this: collectives, societies, are not just lumps of individuals. The social has a power of its own, exists outside of individual minds. It is for this line of thought that sociology became a field at all and is not instead just a subset of psychology.

And this is notably different than physical photos which also age with time, show wear and use like we do.

S. Mann, Hold Still: A Memoir with Photographs

S. Kierkegaard, The Sickness Unto Death. A point worth noting here is his idea of us as a synthesis between finite and infinite. We have constraints to our selfhood — biological, sociological, etc. But the human being also has a kind of infinite potential, be it with the pursuit of passions, realizing projects, learning, shaping one’s reality. The self is played out between these two poles.

It’s tricky language here, and it kind of gets into Heidegger’s idea of a thrown-projection, that the past is actually thrown up ahead of ourselves such that the past isn’t something that is just behind us (as a linear idea of temporality suggests) but part of our living fabric, shaping and projecting our future.

& less footnotes, my friend :)

I liked this: “If Kierkegaard’s self says “I am who I will be,” it’s the prisoner of memory’s that says “I am who I was.”